A somewhat long and rambling consideration of Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolution

In college, I double majored Political Science and Management Science. I now work in a field called Data Science. Even though the last time I sat in a physics class was my junior year of high school, I am a scientist. One of my college buddies, an engineer, liked to poke fun at me, "if they have to put science in the name, I am pretty sure it's not science." Despite my degrees, I agreed with him. Seven years and one PhD later, my thoughts on science have changed. I no longer define science so much by the subject matter as by the process. Science is not limited to applications of physics, chemistry, or biology; human behavior, interactions between people, and society at large can also be topics of scientific inquiry.Science isn't so much defined by subject matter as by a process. This process is, of course, the scientific method: generating hypothesis and testing the hypothesis by observation or experimentation. Unsurprisingly, there is a science of science; which is excellently described (and probably really began) in Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolution. In this book, Kuhn proposes a theory of how large scientific breakthroughs,"revolutions", are arrived at. To do so, he also establishes a framework for how science functions outside periods of revolution. I found this framework both immensely useful for understanding the ebbs and flows of science, but also questioned whether "revolution" is as unique as Kuhn seems to imply.

Normal Science

When I think of a "scientist", generally two images come to mind. The first is Einstein; the solitary genius who over the course of a year published 4 amazing papers, including the theory of special relativity in 1905. Then 10 years later, he solved general relativity. Einstein is essential the platonic ideal for scientific revolutions. The other image I get is Doc Brown from Back to the Future. But, being a little older and wiser in science, I actually don't think he is a much of a scientist at all; where's the theory, the experiments, and the peer review? He's actually far more an engineer, tinkering and building things. I'd like to see the literature review that Doc Brown's committee made him do before he could go build the Flux Capacitor.I bring this up, because I now realize that the prototypical for a scientist is more like my sister, grinding it out in a biology lab in gradate school, checking and maintaining yeast experiments in her petri dishes. This, Kuhn describes, is normal science, "Perhaps the most striking feature of the normal research problems... is how little they aim to produce major novelties, conceptual or phenomenal." Sorry Sis (but keep reading, there's hope).

He describes three main activities of normal science:

- "Attempts to increase the accuracy and scope with which facts...are known occupy a significant fraction of the literature of experimental and observational science". Kuhn describes "some scientists have acquired great reputations, not from any novelty of their discoveries, but from the precision, reliability, and scope of the methods they developed for the redetermination of a previously known sort of fact." One could argue the most recent winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics , Angus Deaton won for estimating demand across countries. Someone described his work as counting things really really well * (though I have more to say about that later)

- "Factual determinations is directed to those facts that, though often without much intrinsic interest, can be compared directly with predictions from the paradigm theory" An example of this is when Arthur Eddington and company confirmed relativity by measuring the position stars during an eclipse, making front page news.

- "Empirical work undertaken to articulate the paradigm theory, resolving some of its residual ambiguities and permitting the solution of problems to which it had previously only drawn attention." I have a lot to say about this particular function later.

Scientific Revolution

Now that I have worked through normal science, let's get to the good stuff: Scientific Revolutions. Essentially, Kuhn argues that revolutions aren't simply the result of a solitary scientist, with a stroke of genius, but instead arise from crises in science.He describes that fields of scientific inquiry have "paradigms": a consensus among scientists of the underlying model of the field. As "normal science" continues, there may be cracks in the paradigm, measurements and experiments begin to expose flaws or inconsistencies. Once enough of these mount, it becomes clear that a particular branch of science is in crisis.

At this point, there is room for a scientist to propose a new paradigm: the scientific revolution. This shouldn't diminish the genius of Newton or Einstein who create the new paradigms. They solved a problem no one else has yet! It's simply that the structural problems of a paradigm create conditions for revolution. They focus attention on where a revolutionary ideas are needed and create an environment where other scientists are even willing to accept the new paradigm. Science still needs those geniuses, otherwise the field can stay in crisis until that great scientist (or team of scientists) come around.

The process of accepting a new paradigm isn't always easy. It's revolution, not unlike the American or French revolution. Some scientists may defend the old order, and it can take years (or even decades) for sufficient evidence to change minds. Also, scientists can be stubborn and defend their own ideas even after they are outdated (even Einstein did this with quantum theory).

Testing the Revolution Hypothesis

Reading his book was convincing and this sounds like a pretty sound theory of scientific change. But I wanted to test this out a little for myself, and wanted to trace through a scientific revolution that I am a little more familiar with. This thought exercise lead me to some interesting conclusions. I want to be clear though, I am not a historian of the economic sciences, and it wouldn't surprise me if someone fact checks points to tell me I'm all wrong. This is me, working though a thought exercise based on my own well-educated, but not expert knowledge.Kuhn's examples are typically in the hard sciences: Copernicus, Newton, Einstein, and Darwin come to mind (he seems to assume some background knowledge in each of these revolutions; despite my title of scientists, I was not as up to speed in these). But he doesn't touch the social sciences, which I know a thing or two about.

According to Kuhn's argument, first thing you would need for a scientific revolutions a paradigm. One of my undergraduate majors was in political science, and so far as I can tell there is not really underlying paradigm. To me, it seems a whole bunch of individual theories and models, that are often each empirically tested. But, there is no unifying underlying paradigm. Best I can tell, the same is true of psychology and sociology.** While there may be new research and measurement, there simply cannot be the type of revolution Kuhn describes.

I believe economics has an underlying paradigm: general expected utility theory. In fact, early economists modeled economic analysis after physics, and took great care to design a scientific paradigm. To describe this as briefly as possible: people have preference and preferences are stable, so they can be described in a utility function. This function is concave which means there is decreasing marginal utility. If you like pizza, the utility provided by going from the zeroth slice of pizza to the first is much higher than than going from the tenth to eleventh. People's behavior can be modeled as maximizing utility, subject to prices and a budget constraint. This is the concept of homo economicus, the hyper-rational person always optimizing to their preferences. And all sorts of results come from this, like that people are averse to risks (which is why we buy insurance).

But, then economists and psychologists started noticing things about this paradigm that didn't quite hold. For example, the same people who buy auto-insurance may also purchase lottery tickets, implying people are averse to some risks but love others. People might not be willing spend a dollar for that 4th slice of pizza, but they also wouldn't be willing to sell that fourth slice pizza for a dollar, implying a persons valuation of a good depends on whether or not they already "own" them. A number of laboratory experiments confirmed insights inconsistent with general expected utility theory. Looking closely at the stock market or other economic transactions, researchers could find evidence of the same behavior. So two researcher, Kahnemen and Tversky, developed a whole new paradigm based on this, prospect theory (which I have alluded to in other posts). Without diving in to much, it posits a different shape of the utility curve, which accounts for loss aversion and some risk-seeking behavior.

Some might say economics is currently in the midsts of a Kuhnian Revolution. The behavioral economists are pushing towards a consensus amongst economists that this is the new paradigm. Traditional economists are pushing back, bending over backwards to show how these "irrationalities" can actually fit in the older paradigm, like Gary Becker's theory of rational addiction.

Well, at least some people will tell the story of behavioral economics as a classic scientific revolution. But, what I realized thinking through this, there might be another way to tell this story. This version would say prospect theory isn't a scientific revolution at all, its really just the third type of normal science, filling in holes and expanding the theory when necessary.

It would say: obviously the behavioral experiments hold. The concave utility function is simply an approximation, but it often works well enough so lets push that as far as it can go. Prospect is still fitting these psychological phenomena into a utility function, its just shaped a little differently. The economic paradigm is really that human behavior can be modeled with a utility function. But there is room in that paradigm to refine our understanding of the function.

Look, I am not sure which story is correct. It's totally possible that someone has written or will write the definitive history of behavioral economics, and it will be clear which narrative it fits into. However, even if the history is clear, the thought experiment points out to me that there is a thin line between normal science and scientific revolution. It may not be easy to describe individual pieces of research as either normal science or revolution, maybe only after the fact can we know what was normal science and what was revolution. And then it follows, there aren't normal scientists and revolutionary scientists: there are just scientists.

A Series of Small Revolutions

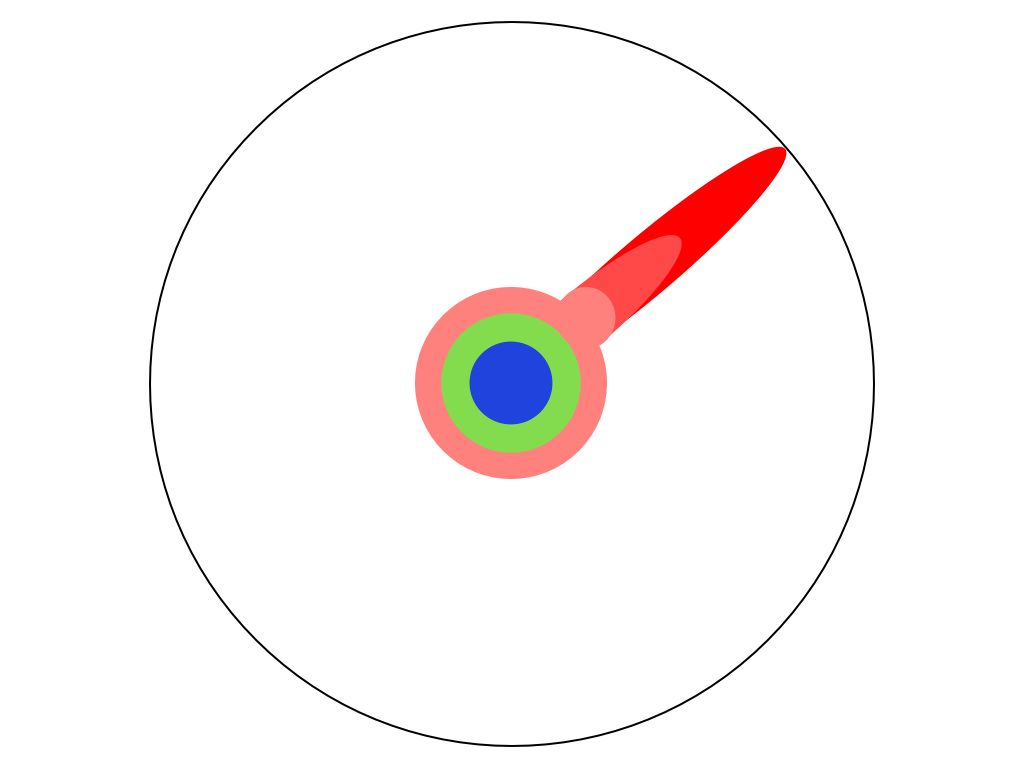

If you look at world history, there are some massive revolutions: The American Revolution, The French Revolution, The Bolshevik Revolution, and The Industrial Revolution. And those only the ones named "Revolutions"! I would probably throw in the Protestant Reformation, The Gutenberg Printing Press, and many many of others. They are hugely important, affect millions of people, and change the course of history. There are also many many smaller revolutions every day. A new CEO takes over a company; that could be considered some type of corporate revolution. Your child turns 16 and gets a car no longer depending on parents for transport; this a familial revolution altering the power dynamic between parents and children.Science is the same way. I have many different ways I describe myself as a scientist, ranging from broad to extremely specialized. I'm a social scientist. I'm an economist. I'm a resource economist. I study climate change. I study climate change in water systems in the Western U.S. A famous blog post describes a PhD as pushing forward knowledge in tiny little domain, illustrated in the picture below. The circle represents all of human knowledge, and the colors represent levels of education, with the red PhD just pushing the frontiers at one tiny little point.

|

| source: http://matt.might.net/articles/phd-school-in-pictures/ |

Is it possible that every sub-domain of expertise has a tiny little paradigm working for it? Maybe Prospect Theory does in fact over-turn the paradigm of strictly diminishing marginal utility, while simultaneously strengthening the paradigm of a utility function. In the course of normal science, people get creative ideas. Maybe its a new way to measure something, or a unique experiment, or just a slightly different model. If this is true, over the course of a 30 year career in "normal science", many scientists generate one or two mini-revolutions.

Angus Deaton, who as I argued before is famous for counting thing, actually had create a whole new way to quantify demand to count the thing he wanted to count*** Now, he didn't overturn supply and demand (fundamental elements in paradigm of economics) to do this, but The Economist argues that this was a paradigm shift of sorts. Sure, he won a Nobel Prize for this, but this isn't the jump from Newton to Einstein. How often does something like that on an even smaller scale occur?

I would argue I had had some unique ideas in my graduate research, which changed the way our little team operated. I'm certainly no Einstein, but maybe I created the smallest (literally the smallest) of scientific revolutions. And is there really a bright line between that, and what many scientists do every day? Sis, I would suspect you are both a normal scientist and revolutionary!

* I am sure I read the characterization of his work as "counting things" somewhere else, but for the life of me I can't remember the source. So first of all, apologies from whomever I am quoting in an unattributed manner. Second, if anyone knows the link, please share! I would love to attribute that description to the right person.

**This is totally me trolling my political science and psychology loving friends. I am almost certainly speaking out of turn, from a place of not much knowledge. Would love for you guys to push back, and point me to the paradigm. Or argue that a paradigm isn't necessary for science!

*** I plan on reviewing this paper at some point

I would argue I had had some unique ideas in my graduate research, which changed the way our little team operated. I'm certainly no Einstein, but maybe I created the smallest (literally the smallest) of scientific revolutions. And is there really a bright line between that, and what many scientists do every day? Sis, I would suspect you are both a normal scientist and revolutionary!

* I am sure I read the characterization of his work as "counting things" somewhere else, but for the life of me I can't remember the source. So first of all, apologies from whomever I am quoting in an unattributed manner. Second, if anyone knows the link, please share! I would love to attribute that description to the right person.

**This is totally me trolling my political science and psychology loving friends. I am almost certainly speaking out of turn, from a place of not much knowledge. Would love for you guys to push back, and point me to the paradigm. Or argue that a paradigm isn't necessary for science!

*** I plan on reviewing this paper at some point

You're right that there's a thin line between a revolution and normal science, especially after a field already has a dominant paradigm. You could also draw distinctions between revolutions that really overthrow an essentially incorrect paradigm (modern medicine vs humour theory for instance) and revolutions that preserve and redefine essential parts of the previous theory, showing it to be true under specified conditions (General Relativity vs Newtonian gravity). But one thing that can make scientific revolutions pretty different from normal science is that they can lead to a change in world view. I haven't gone back to the book in awhile but just reread a different author's introduction to it and this stood out to me, and also fits with my recollection of Kuhn's The Copernican Revolution. Given that an object's position in space is relative, we know there's no fundamental truth to whether the Earth revolves around the Sun or the Sun revolves around the Earth, and Copernicus's system wasn't actually mathematically simpler than what came before nor more accurate. But Copernicus's system engendered a change in world view that made possible a better mechanistic account of planetary motion from Kepler and Newton. So perhaps whether the differently shaped utility curve constitutes a revolution in economics depends on how significant the accompanying change in world view is, independent from the extent to which it provides more accurate quantitive predictions.

ReplyDelete